The Discovery of Comet Machholz 2004 Q2

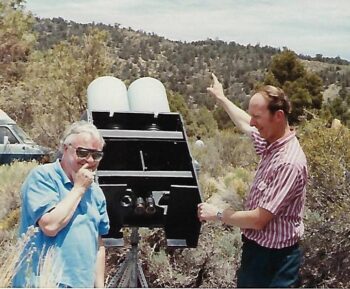

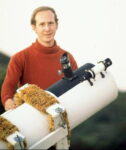

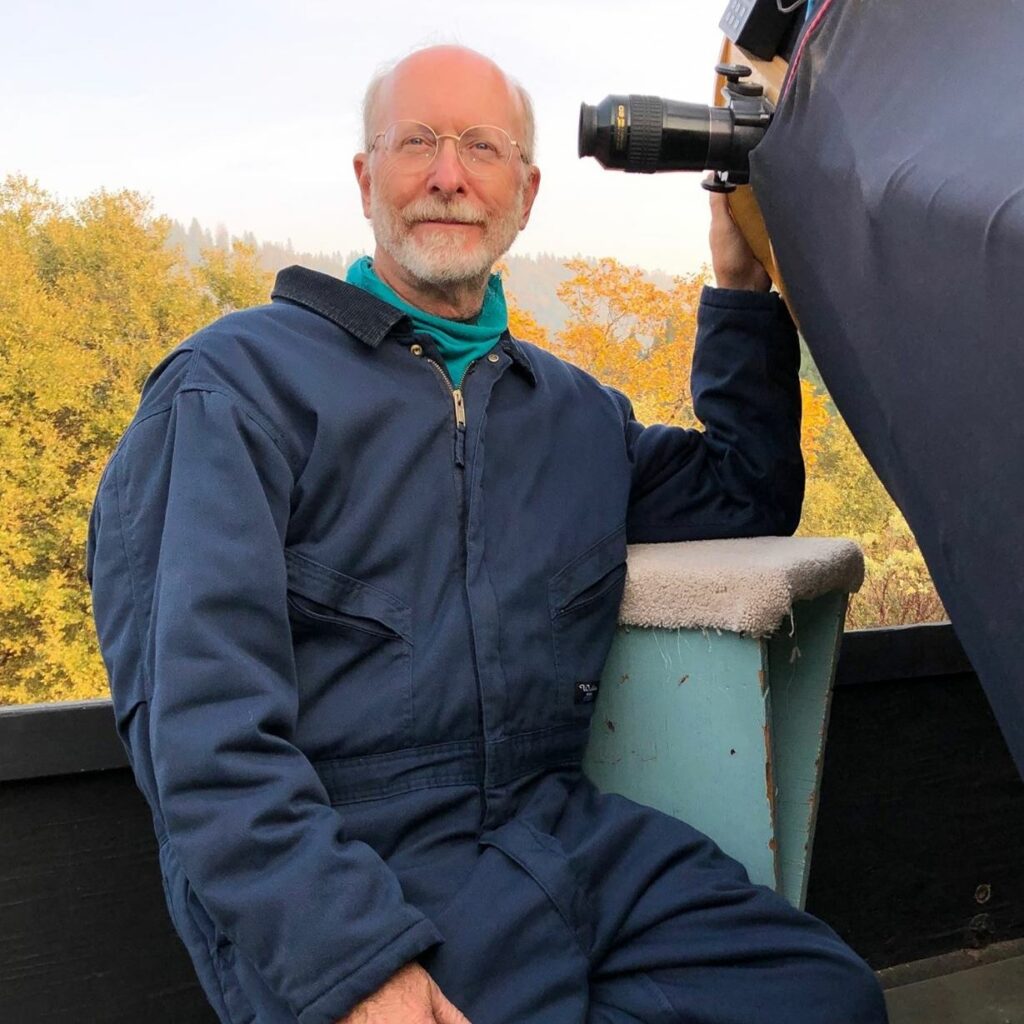

When I awoke at 3:20 on the morning of Friday, August 27, 2004, I knew what I wanted to do and why I was getting out of bed three hours before normal. This was a morning for comet hunting from, of all places, my back deck. This is rare, as I have a homemade observatory 100 feet from my house, and I use it for most of my comet hunting. In it are my 10-inch reflector (with which I have found four comets); 5” homemade binoculars (four comets); and an unmounted 5” homemade refractor sitting in the corner (one comet). I had used the 10” reflector and 5” binoculars for searching earlier in the month to cover much of the morning sky, now I would use a different instrument on my back deck to cover the southern sky.

The telescope for this morning’s session is a 6-inch, f/8 reflector Criterion Dynascope, one that I bought in 1968 for Christmas. It cost $200 and I paid all but $50 for it (my folks paid that). This telescope has very good optics and the main mirror still has its original coating. It has a clock drive (my only telescope to have one), and I use this telescope for all the public and private star parties I do each year. The eyepiece I was using this morning has a 2-inch outside diameter which I have adapted to fit over the eyepiece holder to provide a field of view of about 1.8 degrees. The magnification is about 35. I often use this combination to show M24 at dark site star parties. Sometimes our guests say that this was the best thing they saw that night. I also use this setup for conducting the Messier Marathon, finding all 110 Objects from memory last spring from the desert in Southern California. This telescope/eyepiece combination is very comfortable to me. I had been out two mornings before, covering the first half of the area. Now I’m back for more.

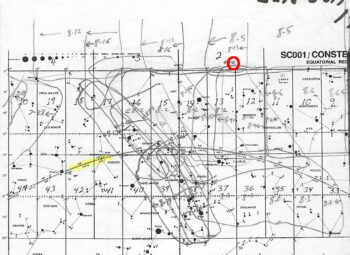

After moving the American Flag out of its mount on the corner of the deck and leaning it against the railing in order to get it out of my view, I began at 3:35 a.m., picking up where I had left off in the southern sky. I look through the eyepiece with my right eye, with an eye patch on my left, and slowly sweep southward to the horizon. At the end of each sweep, I raise the telescope to the beginning position, move it slightly east, and sweep again. There are a lot of galaxies in this area, and I picked up a few: NGC 1316, 1398, 1395, 1399, 1404 and a planetary nebula, NGC 1360 (which I had once accidentally reported as a possible comet in 1977). With each of these objects, all looking like faint comets, I confirmed that they were not comets by checking them against my Skalnate Pleso Atlas of the Heavens charts that I had with me at the telescope. This chart shows most of the galaxies and nebulae that I would normally pick up while comet hunting.

At 4:12 I picked up a faint fuzzy object, rather small. I looked closely to see if it was a double star or a small grouping of stars that simply appeared fuzzy. It was not. I then grabbed my star map to see if there were any known galaxies or nebulae in the area. It took me a couple of minutes to determine exactly where I was on the star map. There was nothing shown on the map.

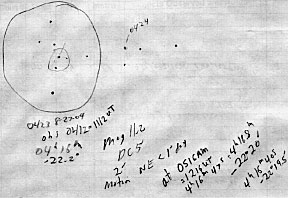

A more detailed star atlas sat in my observatory. Our dog Shadow and I went out to the observatory to bring back the Uranometria 2000 atlas. It showed nothing. I marked the location on the map with the date and time. At this point I made a drawing of the area, showing the location of the comet in relation to the surrounding stars. If it is a comet it should show motion in an hour’s time. This detailed drawing would help determine both the rate of travel and the direction of travel. This drawing was made to show the view I had in the telescope, with south to the top.

An even more detailed star atlas is on the computer in my house. We (the dog follows me everywhere) went inside and turned on the computer, bringing up a program called “The Sky.” It showed a couple of very faint (magnitude 15) stars in the area, too faint for me to see.

There is a chance that this could be a known comet. At any time there are a few previously discovered comets visible in the sky—perhaps this was one of them. I went to the Internet to a site which lists such comets Aerith It showed no comets in the area.

By now it was 4:37 a.m. I had first seen the object 25 minutes ago and had 40 more minutes until morning twilight would interfere with my view of it.

I then went out to the observatory and uncovered the 10-inch reflector. I quickly found the location and put in an eyepiece giving 64x. I could see that the object was fuzzy, round and made a mental note of where it was in relation to the nearby stars. It seemed to me like it had moved a bit. I also uncovered the 5” homemade binoculars and examined the comet. In this instrument, it was difficult to see, but it was visible.

I then went back into the house and tried to wake up the family. My wife at first did not want to get out of bed to look at it. I tried waking my two sons but neither wanted to get up to see it—they were too sleepy. When I went back out onto the deck my wife came out and tried to see it, but could not make it out very well due to its faintness. I came back into the house and began writing up the report that I would need to send to the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT) in order to get the comet confirmed and recognized. They are the clearinghouse for new comet discoveries.

Also during this time, I went online to see if this part of the sky had been covered by the automated search programs. It wasn’t. During the past few years, there have been an increasing number of large government-sponsored telescopes patrolling the sky for asteroids and comets that may one day pose a threat to the earth. In the course of these nightly, automated searches, these instruments pick up many of the comets that amateurs would normally find. The comets are named after the programs that find them: LINEAR, NEAT, LONEOS, Spacewatch, Catalina. They search areas away from the sun, and the locations they have searched are plotted on the Internet. As if this isn’t enough, a spacecraft named SOHO covers the area near the sun, its images are posted on the Internet and anyone viewing them can find (usually) tiny comets that evaporate as they approach the sun. These comets are named SOHO. The SOHO spacecraft also has a camera system (named SWAN) covering the remainder of the sky. It, too, has discovered comets.

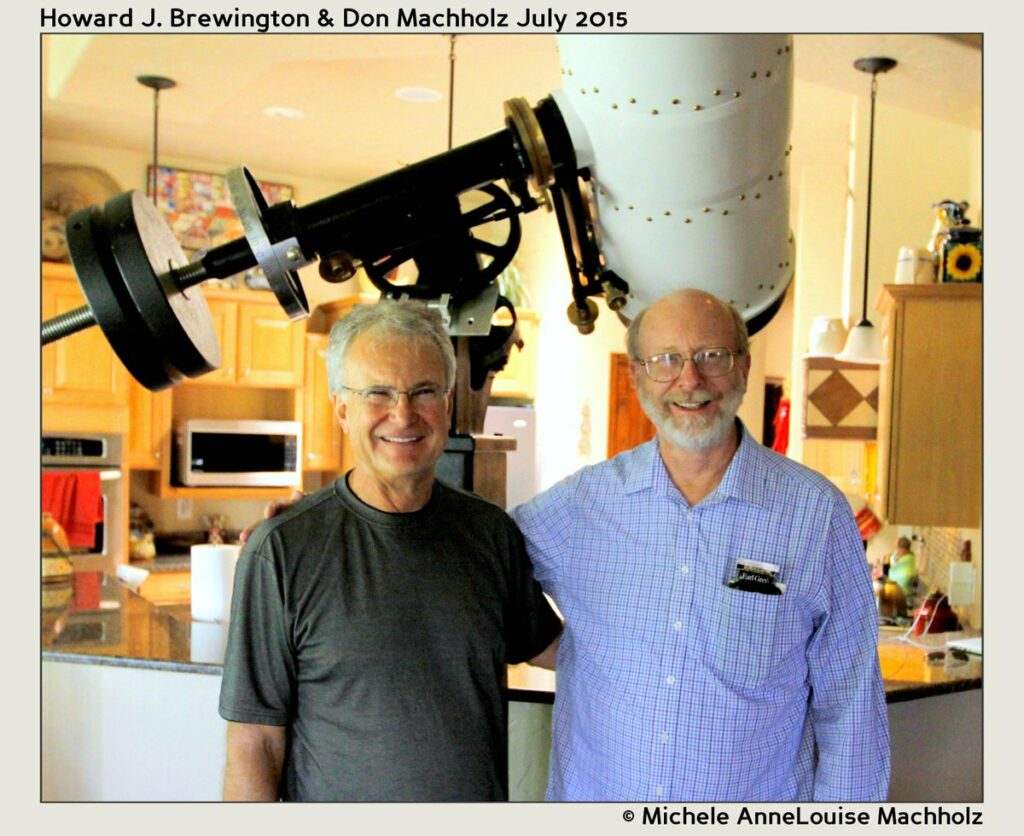

With the advent of such searches, many amateurs have ceased visual comet hunting. Some have turned to using CCDs attached to their telescopes, which cover a small area of the sky with each image and can see very faint objects. These amateurs are trying to beat the automated searches at their own game. I have continued my visual comet hunting, nonstop, searching for at least an hour per month each month since I began on January 1, 1975. In the past I have done up to 553 hours of searching per year, presently I’m doing about 100 hours of searching per year, tailoring my searches to parts of the sky most likely to yield comets. This is based on a lot of factors, including knowing where the automated searches have been.

Shortly after 5 a.m., I was out at the 10” telescope, making an estimate of the comet’s brightness, size, and shape. It had no tail. It was also showing some movement toward the east, and perhaps, it appeared to me, slightly to the north. I later learned that its actual motion was 20 arcminutes (one-third of a degree) per day to the east and slightly south. So in one hour’s time, it had moved less than an arcminute—a very small amount. Finally, the twilight was so strong I could no longer see the comet, so I came in to report it.

I searched for 1458.25 hours since my previous find (of my ninth comet) nearly ten years ago. (One does not include my independent discovery of Periodic Comet de Vico on September 18, 1995, which does not carry my name). I have searched for 7047.25 hours since I began comet seeking on January 1, 1975, nearly thirty years ago.

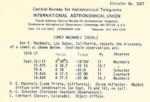

I assembled the e-mail and sent it to the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT). I then faxed the same message to them. A follow-up phone call confirmed that the message had been received. I got ready to go to work; I work as a research and development technician at Coherent, a laser and optics company. I also work as a real estate appraiser.

It was six hours before I heard the news from Dan Green of the CBAT. The comet was confirmed, imaged by Robert McNaught and G. Garradd. It was named Comet C/2004 Q2. The next day “(Machholz)” was added to it.